Wolf population stabilizes near state’s sweet spot

Problems with wolves and killing of wolves are down in past two years, biologist says.

Wyoming wolf numbers have settled in right around 300 animals, near population levels that wildlife managers sought before numbers climbed when hunting was prohibited between 2014 and 2017.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department regained authority over Canis lupus that April three years ago and held hunting seasons in subsequent falls. The first two years the population fell, followed by a slight increase in 2019. Now the numbers are right around the target, Game and Fish wolf biologist Ken Mills said.

“I think we’re really settling into a pattern that is outlined in the wolf management plan and an objective we’ve had as an agency,” Mills told the News&Guide, “that is to reduce the population and stabilize it around a number that’s above the minimum recovery criteria while also reducing conflicts and reducing the number of wolves we take as an agency.”

The intricacies of wolf population dynamics in Wyoming’s portion of the Northern Rockies are laid out in an annual monitoring and management report that Game and Fish published last week. It’s attached to the online version of this story at JHNewsAndGuide.com.

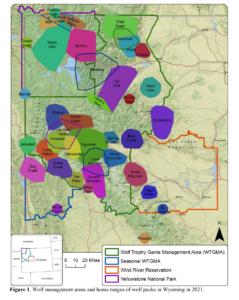

Although the estimated year-end Wyoming population registered at 311 wolves in 43 packs, the state has jurisdiction over just a portion of those animals.

An estimated 94 wolves running in eight packs were documented within Yellowstone National Park’s 2.2 million acres. Some 16 wolves in three packs were detected on the Wind River Reservation. Another 26 wolves were picked up during surveys on the peripheries of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem within a “predator zone” covering 85% of Wyoming where the state imposes no restrictions on killing wolves and doesn’t promote having the species on the landscape.

That leaves 175 wolves in 27 packs in the “trophy game area,” where the Wyoming Game and Fish Department has jurisdiction and the ability to sway the population this way or that. That number is close to the agency’s biological objective of 160 animals — a number meant to meet or slightly exceed the Endangered Species Act delisting requirement of 10 breeding pairs.

Mills sees benefits to keeping wolf numbers near that mark.

Conflict with livestock, for one, has been down significantly the past two years. During 2019 there were 42 cattle, 27 sheep and either a horse or donkey confirmed killed by wolves, according to Game and Fish’s monitoring report. In 2016 and 2017, when the wolf population was larger and hunting prohibited, depredation numbers were nearer 200 livestock confirmed killed annually.

Compensation to cattlemen and woolgrowers fell apace. Wyoming Game and Fish payments in 2019 totaled $106,000, down from reimbursement figures nearer $400,000 during 2016 and 2017.

Numbers of wolves killed in retaliation for preying on livestock also fell. Last year there were 30 wolves lethally targeted, down from 113 at the high point in 2016 and approximately 60 wolves killed the two years following.

Documented wolf mortality declined in general. A total of 49 wolves were killed in the state-sanctioned hunt and in the predator zone. Factoring all causes, 92 wolves are known to have died outside of Yellowstone and the reservation in 2019, which is 50% of the toll during the year before.

Mills said that prevalence of diseases like mange and distemper have fallen off from rates observed a few years ago, likely because the population density has also dropped.

Wyoming monitors its wolf population with much more precision than neighboring Idaho and Montana because the population was deemed “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act within the past five years and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service requires a detailed annual assessment.

In the Equality State, biologists with Yellowstone, the Wind River Reservation and Mills aim to count wolves one by one, essentially conducting a census of the whole population. They use GPS and very-high frequency tracking collars to accomplish the task, and a high proportion of the overall population is fitted with telemetry equipment. As of March, Game and Fish had tracking collars on 83 wolves in 27 packs — 41% of the population outside Yellowstone and the reservation.

That level of detail allows biologists to keep tabs on individual packs and where they roam with precision.

Among the most notable changes to Jackson Hole wolf packs this past year was a distribution shift and a territory swap triggered by the 17-wolf Huckleberry Pack moving south. The 10-wolf Pinnacle Peak Pack, longtime denizens of the National Elk Refuge, were run off their turf — and they remain north and east of the refuge today, Mills said.

Other Jackson Hole wolves in the mix include the 12-member Lower Gros Ventre Pack, and the two-wolf Lightning Pack and four-wolf Togwotee Pack up the Gros Ventre River drainage. The nine-wolf Pacific Creek Pack called the northern part of Jackson Hole home at the end of 2019.

South of town dwell the seven-animal Game Creek Pack, which broke off from the now-defunct Horse Creek Pack and raised a litter. Seven wolves were running in the Dog Creek Pack, and another eight were observed in the Dell Creek Pack in the Hoback Basin.

Mills said he has an eye on three wolves in central Jackson Hole that he has hesitated to call a pack because they haven’t yet produced a litter. But those wolves, which Grand Teton National Park has been referring to as the Murie Pack, could give birth to pups any day.

“It’s quite likely they have a pregnant female, and it’s a matter of where are they going to put a hole in the ground,” Mills said. “I’ve got a pretty good idea of what they’re going to do — use the territory from what was the old Lower Slide Pack. That looks like where these guys are going to try to stake a claim.”

Contact Mike Koshmrl at 732-7067 or env@jhnewsandguide.com.