Part of Wyoming Untrapped's mission is informing the public of the hazards of Wyoming’s inhumane wildlife trapping practices. WU wrote this issue overview in 2014 as a way of conveying those hazards and providing insight into the realities of trapping in Wyoming. Visit our news section for updates on the issues outlined here.

History & Practice of Trapping

Humans have trapped animals for food, fur and other uses since before recorded history. In Wyoming, the fur trade is believed to have begun as early as the 1740s, when French fur trader Pierre de la Verendrye began trading with Native Americans in the Big Horn Mountains.

According to the Wyoming State Historical Society records, Francois Antoine Larocque traded for furs in the Powder River area in 1805.1 But it wasn’t until after 1806, when the Lewis and Clark Expedition reached the Pacific Coast, that trading accelerated in Wyoming. The expedition reported that beaver and their prized pelts were plentiful in the Mountain West, and the stream of explorers seeking their fortunes followed.

Two members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, John Colter and George Drouillard, traded with Native Americans for fur in Wyoming as employees of the St. Louis-based Manuel Lisa fur company. While uncertainty remains, Colter is believed to have trapped in the Cody area, along the Shoshone River and into parts of present-day Yellowstone National Park.

Fur Trade Expands

As popularity and demand for fashionable beaver fur hats increased in Europe, prices increased as well. In turn, more fur-trading companies emerged. John Jacob Astor created the Pacific Fur Company in 1810, and others entered the scene as well. Employees of Astor’s company traveled overland west, toward the mouth of the Columbia River. They crossed Wyoming and traveled over the Wind River Mountains at South Pass. From there, the contingent spotted the Tetons and the Snake River, which they followed to the Columbia River and the Pacific Coast.

Steel trap mass-produced

Until 1810, most fur was acquired from Native Americans, who traded with Europeans for guns and other goods. In the early 1820s, European explorers began their own trapping, when steel leg-hold traps began to be mass produced and widely available.

Between 1820 and 1840, smaller fur companies engaged in the trade, and competition intensified. Trading posts, or forts such as Fort Bonneville on the Upper Green River near Daniel, Wyoming, were built. During this time, annual rendezvous, or trading fairs, began as well. Various alliances between Native American tribes and European traders developed, and battles between these alliances and individual tribes sometimes occurred.

Collapse of an industry

By 1840, tastes in fashion had changed from beaver fur hats to silk. Demand dramatically decreased. Simultaneously, the beaver population was collapsing. Other furs less expensive than beaver began to be used for felting. It became increasingly difficult to make a living in the beaver trapping and trading industry.

Bison and Wolves

During the 1850s and 1860s, demand for beaver fur also shifted to that of bison, deer, elk and wolf. Ubiquitous on the landscape, wolves benefitted from the thousands of bison slaughtered, feeding on the remains left once the animals were skinned. Between 1860 and 1885, wolf pelts became increasingly valuable. The preferred method to kill wolves at that time was not traps, but poison. “Wolfers” would kill and skin a bison and lace the remains with strychnine, and leave the bait. They would return a day or two later and collect pelts.

Fate of the Wolf Sealed

Once bison were nearly wiped out through the 1870s and into the early 1880s, settlers turned to big game animals for a source of meat. Entering the 1890s, settlers had hunted most big game species to numbers that today would qualify them to be listed as endangered species. With much of their prey species disappearing, wolves naturally turned to an increasingly plentiful food source: cattle. As big game disappeared, cattle ranchers from other states like Nebraska and Texas began moving operations to Montana and Wyoming. These critical events — decline of big game and increasing abundance of cattle —determined the fate of the wolf. It became the enemy to both hunters seeking the same prey and ranchers protecting their property. The era of aggressive wolf and coyote trapping began then and persists today.

Wyoming Trapping Today

Most Wyoming folks today have at least a vague sense of the state’s trapping history. Many, however, assume that the practice has largely disappeared. That, of course, is not true. Tens of thousands of furbearing animals and predators are trapped every year in Wyoming alone. Hundreds of thousands are trapped throughout the United States. Except for some restrictions in some areas for marten and beaver, there are no limits on how many furbearing animals can be harvested during the season.

Trapping harvests

For the state’s 2012-2013 trapping season, The Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD) recorded 12,296 furbearing animals harvested. Muskrat led the way with 4,837 killed. For beaver, the number was 2,700. The total for bobcat was 1,800, while marten accounted for 1,237 of the total harvest.

Annual harvest reports are based on surveys that furbearer trappers and hunters are asked to voluntarily complete. The surveys are mailed to all who were issued licenses. The return rate for the 2012-2013 season was 27 percent. WGFD extrapolates total harvest numbers based on the completed surveys.

The WGFD counts only furbearer animals harvested. They include badger, beaver, bobcat, marten, mink, muskrat, or weasel.

Bobcat are not counted using the voluntary survey method. Instead, trappers and hunters have been required since 1990 to present pelts for inspection and tagging. The requirement is rooted in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Because bobcat look similar to some protected species, such as the Canada Lynx, wildlife managers want to ensure no protected species are being killed. For the 2012 season, 1,651 bobcats were trapped, and 209 shot.

Besides the Canada Lynx, other protected species in Wyoming include black‐footed ferret, fisher, otter, pika and wolverine.

Predators not counted

In 2010, WGFD stopped including predators in the total harvest count. Counting predators in the previous year, 2009, the total harvest was 33,035.

Animals classified as predators include coyote, jackrabbit, porcupine, raccoon, red fox, wolf, skunk or stray cat. They can be trapped any time, anywhere, in unlimited numbers. Predators fall under the jurisdiction of the Wyoming Department of Agriculture.

“Non-target” animals trapped

The total number of furbearers and predators trapped and killed each year does not include the “non-target” animals inadvertently trapped, including domestic pets. Trappers are not required to report non-target animals trapped, whether they are killed, injured or safely set free. Trappers are required only to report game and protected animals trapped and killed or injured seriously enough to cause death. Game and Fish, however, does not keep records on those incidents.

Some national studies have estimated that as many as two non-target animals are trapped for every one targeted animal. If that estimate is used as a guide, the total number of target and non-target animals trapped each year in Wyoming could approach 100,000, including predators. If only one non-target animal is trapped for every targeted animal, the annual total of trapped animals would be more than 66,000.

While many non-target animals are released unharmed from leg-hold traps, not all are. At least one study found that as many as 50 percent of all animals trapped would sustain cut skin injuries or worse. Injuries worsen the longer the animal remains in the trap. Trappers are not allowed to simply kill a non-target animal, unless it could pose a real threat to the trapper if release was attempted.

Issued licenses dramatically increase

Between 2000 and 2010, the number of furbearer licenses issued in Wyoming increased by 42 percent. That number increased from 1,084 to 1,880. Between 2008 and 2011, the number of licenses stabilized at around 1,900, fluctuating up or down no more than 68. From 2010 to 2012, however, the number increased by 28 percent to 2,636. The dramatic increase in only two years likely was due to a pelt prices hitting a 30-year high.

For a relatively small monetary investment, a bobcat trapper can enjoy a good return. Annual licenses to trap furbearing animals and sell pelts in Wyoming costs $96. A trapper can sell a premium bobcat pelt in good condition and properly processed for as much as $800 at 2014 prices.

The WGFD does not limit the number, type or size of traps set by each license holder. Drawing on trapper surveys returned to the WGFD, officials estimated 15,440 steel spring-loaded traps were set and another 7,150 snares used during the 2012-2013 season. The total number of traps, therefore, was 22,590, not including predator traps.

Trapping seasons, traps and regulations

WGFD regulates trapping seasons, quotas and the practice of trapping as explained below and in the WGFD regulations brochure.

Trapping seasons for most furbearing animals is October 1 through April 30. Seasons for bobcat and marten are Oct. 1 through March 1. There are no seasons for predators such as coyote and fox. Wolves are considered predators, and can be trapped in most of the state most of the time, except for the 15 percent of the state in the northwest identified as the trophy-hunting zone. Wolves also cannot be trapped in an area south of Jackson from Oct. 15 through the end of February.

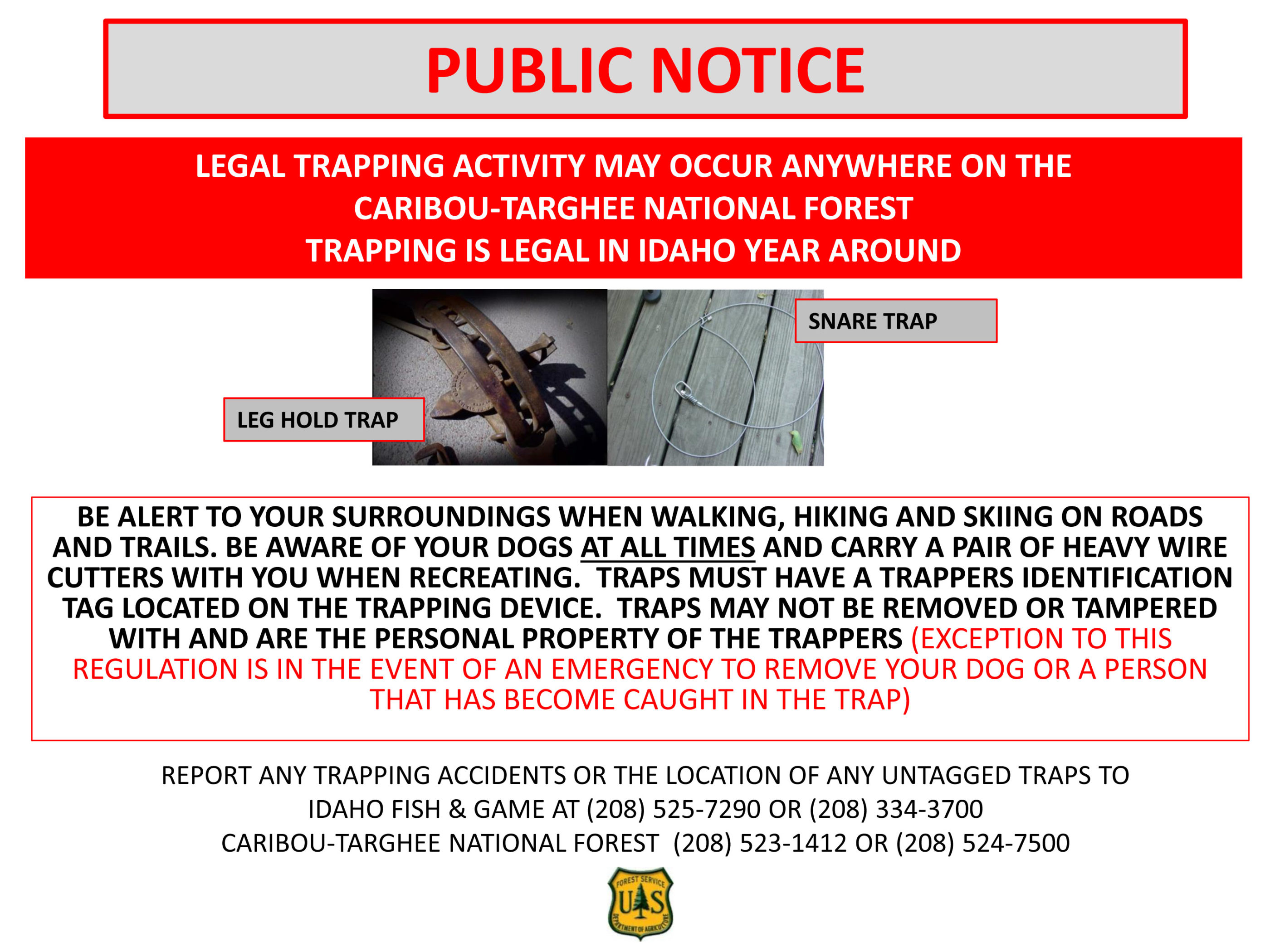

A conibear trap.

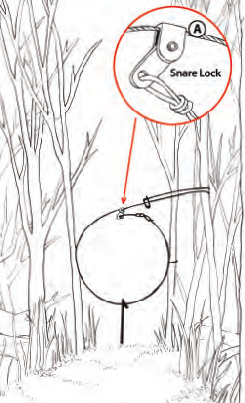

Diagram of a snare.

Leghold trap. Photo by Andy Barron.

Types of traps

- Leg-hold traps: Probably the most well known, this is the steel-jaw trap, triggered when an animal steps on the steel plate in the center. The jaws snap shut on the animal’s leg or foot. The trap is tethered by a cable or chain to an anchor buried in the ground. The animal is attracted to the trap area by nearby bait, often urine or other attractant. The bait is placed in a hole and strategically positioned so that the animal will step into the trap when it investigates the bait. There are many different sizes and styles of leg-hold traps. Trappers are required to check these traps at least every 72 hours in Wyoming.

- Snares: Snares are simple, inexpensive cable devices that typically are suspended along a trail known to be used by the target animal Wyoming regulations require the device to have a breakaway component that will break and release when 295 pounds of pressure is applied. The intent is to allow game such as deer or elk to escape the snare. Trappers will often use visual attractants such as a shiny disc hanging near the snare to draw the animal in. Depending on when a snare is set, a trapper may have up to 13 days between check times.

- Conibear or quick–kill traps: Also referred to as body-gripping traps, these are powerful and intended to instantly kill animals, often clamping on the head. Like snares, check times for these devices could be up to 13 days.

- Live traps: Cages of various sizes designed to entice the animal inside, where it will trip a mechanism that will close the trap and capture it alive.

Bait

The use of game meat or parts of a game animal to bait a trap is prohibited. No exposed carcass or part of an animal weighing more than five pounds can be within 30 feet of a trap.

Trap identification

All traps used to trap furbearing or predatory animals in Wyoming must be marked or tagged with the owner’s name and address or ID number issued by the Department of Game and Fish.

Legal possession

Wildlife caught in any trap is considered to be the property of the trapper. It is illegal to release an animal from a trap owned by another person. It is illegal to tamper with or spring a trap owned by another person.

Disposition of trapped wildlife

Trappers are required to immediately kill or release targeted animals caught in a trap, unless the trapper is licensed to capture and keep furbearing animals. All non-target animals must be released. Game and protected species caught and seriously injured or killed must be reported to the Department of Game and Fish. Trappers have no legal responsibility for a trapped domestic animal, whether it is a dog or livestock.

Trapping setbacks and closed areas

Trapping is allowed on most public lands in the state. Trappers cannot place traps within 30 feet of the edge of a designated road. These restrictions do not apply to two-track roads that aren’t officially numbered or to hiking trails. Examples of closed areas are Grand Teton National Park and Yellowstone National Park and the National Elk Refuge. Some other wildlife refuges throughout the state, such as Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge, may allow limited trapping by special permit, primarily for beaver. Some areas such as Cache Creek in Jackson are closed to beaver trapping. The Rawhide Wildlife Management Area northwest of Torrington is closed to all trapping October 1 through February 15. WGFD owns the land, and decided to close it to trapping during that time after a bird hunter’s dog was killed in a trap.

Buying and selling pelts

Trappers who plan to buy or sell pelts of furbearing animals must obtain a fur dealer’s license from the state.

Prohibitions

The use of an aircraft, motor vehicle or snowmobile to harass or pursue wildlife is prohibited, except for predators. The use of artificial light to hunt wildlife, except predators, also is prohibited.

Wyoming Untrapped Recommendations for Change

Among the 50 states in the nation, Wyoming gets a D+ grade from a 2012 Born Free USA survey of state trapping regulations.8 This is only one indication that Wyoming’s trapping regulations are antiquated and in serious need of reform.

Despite claims by trapping associations and individuals that trapping is a “highly regulated” activity, that simply is not true. Regulations vary widely from state to state, and Wyoming’s are some of the most relaxed.

Trapping is a practice that kills thousands of furbearing animals in Wyoming every year. Trapping also kills and injures thousands of “non target” animals, including domestic pets. Some studies indicate that twice as many non-target to target animals are killed.

For the 2012-2013 season, Wyoming issued 2,636 trapping licenses, a 28 percent increase from the 2010-2011 season of 1,880 licenses. The surge was likely due to strong demand for fashion fur from China and Russia, which has driven pelt prices to a 30-year high. The number of licenses issued between 2000 and 2013 more than doubled, from 1,084 to 2,636. More traps and trappers will mean more problems associated with the practice.

Despite this increasing number, it represents a small percentage of the state’s population of nearly 600,000. Compared to the millions of tourists who visit the state each year, the number is miniscule. This tiny group threatens the safety of all people and pets that use our public lands.

Trappers can place traps almost anywhere on public lands, including in the middle of a hiking trail. While fur trapping is restricted to the winter season, trapping for predators such as coyote and fox can occur year round and requires no license. The public will never be safe on public lands until trapping is reformed.

The most commonly used trap is the leg-hold, steel-jaw trap. Because of the injuries it causes, this trap has been declared inhumane by the American Veterinary Medical Association and the American Animal Hospital Association. This trap has been banned or severely restricted in 80 countries and eight U.S. states.9

The body-gripping, quick-kill Conibear trap has been banned in five states. While it is intended to kill quickly, it does not. Born Free USA research found that approximately 40 percent of animals caught in a Conibear trap die slow, painful deaths due to crushed abdomens, heads or other body parts.10

Snares are inexpensive, simple and also do not instantly kill animals caught. They are intended to strangle animals. Small animals usually strangle within five to 10 minutes. Larger animals, however, can suffer for days before dying. Twelve states have banned snares.

Short of an outright ban on traps on public land, we believe the need for reform is obvious and urgent.

Regulatory changes needed

Area Closures and setbacks

Areas that are heavily used by hikers, bikers, skiers and other recreationists, especially those where many dogs enjoy running free, should be closed to trapping or setbacks increased. As the practice of trapping increases with market demand for furs, so also will the hazards posed to children, adults and pets. Areas used for bird hunting with dogs also should be closed to trapping. Many bird dogs have been killed in the large Conibear traps. Public lands should be enjoyed by all, and not just by the few who exploit them for their own gain.

An alternative to complete closure of an area could be increased setbacks from roads and the creation of setbacks along heavily used trails. Currently, trappers cannot place snares or conibears within 30 feet of the edge of a designated road. Legholds are an exception. No restrictions apply to trails.

We will work with authorities at the federal and state level, as well as with groups and individuals to identify areas and advocate for their closure. We will follow the example of those in other states who have successfully increased setbacks or closed areas to trapping. In Montana, several groups have succeeded in increasing setbacks in popular areas by as much as 500 feet. They are in the process of identifying more areas for expanded setbacks. We have been in touch with these groups so that we can learn and apply their strategies here in Wyoming.

Signs

Where areas cannot be closed or setbacks increased, numerous warning signs should be posted. The US Forest Service has cooperated in placing temporary laminated warning signs at trailheads during the winter trapping season. We recommend permanent signs, since predator trapping can occur year round. We also recommend more signs, perhaps on smaller posts along popular routes, to ensure that if the trailhead sign is missed, others will not be.

Signs like this one could be placed more visibly near trailheads and campgrounds.

Traps like this one can be placed very close to roads, and right along trails in Wyoming.

Trap check times

Trappers in Wyoming are required to check their leg-hold traps at least every 72 hours. Currently, 26 states require a 24-hour trap check period. Western states with this regulation include California, Colorado, Arizona, Washington and New Mexico.

Researchers and trappers themselves recognize that early-morning trap checks every 24 hours significantly reduce injury and suffering to target and non-target animals. We believe the state of Wyoming should acknowledge in its regulations the best practices recommended by the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. That organization recommends 24-hour check times.

For quick-kill Conibear traps and snares, the check time period could be as long as 13 days, depending on which day of the week the trap or snare is set. This regulation provides too much latitude and flexibility to assure a reasonable measure of well being for animals. We believe the check time period should be changed to no more than 72 hours, or ideally 24 hours.

Require safer practices

Some states require that the quick-kill Conibear traps be elevated from the ground by at least five feet to prevent dog trapping. In Michigan, a group of people is pushing for trapping methods that would better ensure safety for dogs. The group has recommended that Conibear traps be placed in a rectangular wooded box and attached to a post or tree at least five feet off the ground.

Furbearing animals targeted with this trap, such as martens, can climb the tree or post and enter the box from above.

To protect dogs, some states also require raccoon traps that allow the animal to reach into a tube for bait, and in the process pull a lever attached to the bait, springing the trap. Such a trap can only be triggered by a pulling motion a dog is incapable of.

Another ground trap specification that can keep dogs safe is to limit the box size containing the Conibear trap, making it difficult for most dogs to enter with their snout. Additionally, the trap can be recessed in the box at least 12 inches, placing it largely out of reach for most average size dogs.

Require complete reporting

Harvest reports

Currently, trappers are not required to report the amount of animals they trap, whether it is a target or non-target species. They are only required to report if a game animal or protected species is trapped and injured to an extent that it will die or did die. While this reporting is required, WGFD does not maintain records on such incidents.

WGFD mails a questionnaire to licensed trappers, and asks them to voluntarily complete and return it. The latest return rate was 27 percent. From those completed forms, WGFD extrapolates the total harvest for all furbearing animals, except predators. WGFD stopped counting predators in 2009.

Fifteen states require such reporting.

Location reporting

Mandatory reporting of trap numbers and locations to WGFD would allow wardens to check to see if trappers are checking their traps as often as required. Otherwise, wardens randomly check areas historically trapped and believed to be prime habitat.

Non-target reporting

Trappers also should be required to report all animals trapped, whether target or non-target, and to indicate the condition of non-target animals when released. Trappers also should be responsible for contacting the owners of any dogs trapped and found, if possible, or contact the local Game and Fish office. Only one state, Wisconsin, currently requires reporting non-target animals trapped.

Count predators

To conduct sound wildlife management practices, all species hunted and trapped should be counted. The state should return to the inclusion of predators along with furbearing animals. Wolf kills by trapping or other means must be reported, according to state law.

Require permits for all trapping

Since trapping and killing or releasing wildlife comes with responsibility, we recommend a license be required to trap any animal, including predators. Requiring licenses for all trapping would allow monitoring and result in increased accountability. Predator trapping results in the trapping of non-target species and should be reported.

Trapper responsibility

Trappers should be responsible for any harm caused to people or domestic animals, whether it is livestock or pets. Requiring trappers to be responsible for harm will provide incentive for them to set traps in areas less accessible to people and pets.

Set Quotas for Bobcats

Bobcats are highly sought after animals by trappers because of the high price of their pelts. With prices remaining high, they will be hunted and trapped more heavily and the population will be put at risk. Wyoming has no quotas on bobcat. Eight other states have bans. Wyoming should determine a sound way to measure the population and set quotas accordingly.

People other than trappers use wildlife. Photographers, wildlife tour guides, outdoor recreationists, and many others make up non-consumptive wildlife users.

Non-consumptive Alternatives for Balanced Management

Recent surveys and studies indicate that the number of Wyoming residents and visitors who watch wildlife outnumber and outspend those who hunt and trap wildlife.

In its 2011 survey report, the US Fish and Wildlife Service counted 140,000 resident and non-resident hunters in Wyoming. Another 1,948 held trapping licenses, according to state reports. In contrast, the same survey found that 518,000 residents and visitors engaged in wildlife watching.

The survey indicated that wildlife watchers contributed $350.2 million to Wyoming’s economy; hunters contributed $288.7 million. Trappers added another $18 million.

Hunter numbers flat

Annual surveys indicate that the number of hunters in Wyoming and many other states in recent years has remained relatively flat. Meanwhile, the number of people who watch wildlife has been steadily increasing each year as the tourism economy grows at about 5 percent per year.

This trend eventually will require the WGFD to rethink how it is funded and by whom. Approximately 80 percent of the department’s annual budget of approximately $70 million is funded through hunting and fishing license fees. Much of the remainder is funded through a federal tax on guns, ammunition and fishing gear. But as WGFD operating costs climb, the Wyoming Legislature has refused to allow an increase in license fees. In 2013, the department had to cut its budget by 6.5 percent, or $4.6 million.

Manage for all stakeholders

Wildlife managers in Wyoming and many Western states have prioritized management practices to favor the hunters who fund them.

The number of predators that prey on elk, deer and other species sought by hunters are therefore managed to low levels because hunters believe they compete for the same prey. Wildlife managers also allow open seasons on predators, not to control populations, but for sport. Non-consumptive users like wildlife watchers and conservationists contend that this approach is not necessary and not based on sound science. In short, they believe management is driven by irrational fears and politics.

Non-consumptive users of public resources, however, have no mechanism for financially contributing as hunters do, despite their higher ranking in economic contributions to the state’s economy.

The biggest contributor to Wyoming’s economy is by far the energy sector. Wyoming contains a wealth of oil, natural gas and other valuable deposits such as coal, trona and uranium. For 2012, the industry contributed approximately $10 billion to the state’s economy.

Trailing far behind after energy was the government sector at $4.3 billion. Tourism followed closely at $3.2 billion. Agriculture added $1 billion per year. Livestock accounted for about $800 million of the agriculture sector of the economy.

Parks benefit Wyoming

Wyoming is blessed with seven national parks and monuments. A 2012 visitor survey conducted by the National Park Service’s Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Office found that visitors to Wyoming’s parks spent $721 million in surrounding communities. Most of the millions of park visitors do not come during hunting seasons, so we can safely assume they do not hunt during their visit.

Tourism industry and hunting contribution

Park spending is part of the state’s $3.2 billion tourism economy for 2012, according to the Wyoming Office of Tourism. The total includes a contribution from resident and visitor hunters of $288.7 million and another $463.8 million from anglers, according to the US Fish and Wildlife Service survey. Combined, hunters, anglers and wildlife watchers accounted for $1.1 billion of the state’s $3.2 billion tourism economy.

In reviewing the numbers, wildlife watchers outnumber hunters and trappers three to one, and they outspend them by about 18 percent.

Given the growing size of their contribution to the state’s economy, coupled with the WGFD budget crisis, non-consumptive users believe the time is ripe to identify alternative funding and diversify the WGFD budget and management practices.

A variety of schemes have been discussed and some proposed, but no one solution has gained serious traction so far in Wyoming. Past attempts to diversify the way Wyoming Game and Fish is funded has met with stiff resistance. Since 1938, when the Wyoming Legislature shifted most funding for Game and Fish to license fees, the department has controlled its destiny and catered to those who fund it.

In a December 2012 Wyofile article on the WGFD budget crisis, reporter Geoffrey O’Gara noted that most Wyoming outfitters supported the department’s proposed license fee hikes that the Legislature ultimately rejected. That’s because any alternative funding would threaten the influence they have over management.

“When it comes to license fees and herd objectives, we call the shots,” one outfitter said in the story. “Our (out of state) clients are used to paying over $1,000 for a license. I support what they’re doing. Their cost of business goes up like everybody else’s does.”

A large percentage of the license fee increase would have been borne by nonresident hunters.

Despite their differences, a broad coalition of conservation and sportsmen groups united to urge the Legislature to approve the fee hikes as an investment in the state’s economy.

During the 2014 session of the Wyoming Legislature, lawmakers approved a stopgap funding measure for WGFD. The bill, Senate File 45, will provide $2 million to WGFD for grizzly bear management, once the federal government turns it over to the states. The bill also is aimed at paying the $4.7 cost of health care benefits for department employees.

Ironically, hunters and outfitters, as well as conservationists, are wary of funding WGFD from the state’s general fund, because it introduces politics into the equation.

“There’s always that fear” that they will dictate, Wyoming Wildlife Federation Executive Director Steve Kilpatrick recently told the Casper Star-Tribune. “And that’s why the current structure, which was established in 1938, is to keep it as autonomous as possible.”

Conservationists worry that politicians holding the purse strings for wildlife management will take a hard line on predator management, for example, to appease ranching constituencies.

Supporting this worry was a recent Wyoming Stockgrowers Association resolution that supported general fund support for grizzly bear management.

“We feel that clearly that shouldn’t be on the backs of sportsmen,” Association Executive Director Jim Magagna told Wyofile in 2013.

Finding a revenue source not subject to control by hunters or vulnerable to political manipulation will be challenging for Wyoming.

Other Ideas

Many ideas have been discussed, but only one recently was proposed as a bill in the Wyoming Legislature by Rep. David Blevins of Powell. It proposed creation of an “awards card program.” The card would be sold through the State Parks and Cultural Resources web site. The cost was not specified in the bill, but Blevins said a price of $10 to $20 had been discussed. He said it was intended to raise $500,000 per year.

Those holding the card would enjoy discounts from merchants who agreed to participate, according to the bill. The bill proposed allocating 45 percent of funds to the WGFD; another 45 percent would be dedicated to state parks capital projects. State parks also would be given 10 percent of the revenue to administer the program.

The bill passed the Wyoming House, but was pulled for further study. It will be introduced again in the 2015 session of the legislature.

Sales tax

Some states such as Missouri, Arkansas, Minnesota and Iowa, levy a sales tax for the specific purpose of partially funding wildlife management and habitat preservation. Each state is different, and a detailed analysis of each is beyond the scope of this paper. A thumbnail sketch of one state, however, could shed some light on how alternative funding for resource management works.

In 2008, Minnesota voters approved a 3/8 percent sales tax to establish its Legacy Fund. Each year the state raises approximately $300 million for this conservation and recreation fund.

The Legacy Fund is divided into four sub funds: Outdoor Heritage, Parks and Trails, Clean Water, and Art and Cultural Heritage. The state’s Department of Natural Resources receives 40 percent of the Legacy Fund total and spends it through each of the four programs.

This particular fund is aimed primarily at preserving wild lands through land purchases or conservation easements, maintaining or cleaning up waterways and ensuring hunting and fishing habitat remain protected.

At least one national organization, Wildlife Forever, which purports to advocate for all wildlife, believes the Legacy Fund delivers big benefits.

“This is the next wave for secure funding for conservation,” said Doug Grann, president and CEO of Wildlife Forever, in an email to WU. “I always wondered why other states are so slow to emulate success.”

In addition to his efforts in Minnesota, Grann was involved in initiatives to add sales tax for conservation in Arkansas and Missouri. He currently is involved in similar efforts in North Dakota.

One of the issues that arises in discussions about using a Minnesota approach for Wyoming is our state’s small population size and how much revenue it can generate.

Minnesota has a population of 5.4 million as of 2010, the last US Census count. Wyoming’s population is 576,000. For 2013, Wyoming generated $946 million in sales tax. One half of one percent of that total would generate $4.7 million, which potentially could be used for a range of conservation programs.

The Wyoming Legislature, however, has been reluctant to levy any new taxes. Wyoming Untrapped will need to further investigate to determine whether this could be a viable option to raise non-consumptive revenue for conservation purposes.

License plates

Other states have used various ways to raise money for specific purposes. Specialty license plates are used in Montana, for example, for a variety of organizations to which funds directly flow. The conservation organization Vital Ground had a plate made. It costs vehicle owners $35, $20 of which goes directly to the organization. Last year, the plate raised $71,000, minus costs, for Vital Ground in Montana.

The University of Wyoming had a plate made, and since 2008 has raised $600,000 for scholarships. Such a plate requires approval of the Legislature. Lawmakers have refused to approve any new plates in recent years. The reason is because Wyoming has a small population with a limited number of people buying license plates. Additional plates would spread thin that limited revenue stream, resulting in marginal benefits to organizations after costs are covered.

Conservation stamp

With some exceptions, hunters and anglers who buy licenses in Wyoming also must buy a $12 conservation stamp. Stamp sales raise approximately $1 million a year, and are used for conservation programs. Programs offering the voluntary purchase of conservation stamps in other states have met with limited success, according to a Wyofile article.

Tax recreational equipment

The idea of taxing the recreational equipment goods used by non-consumptive users is an idea discussed by many through the years. The tax could be similar to the federal Pittman-Robertson 11 percent tax levied on consumptive sporting goods like rifles, ammunition and fishing gear. That federal revenue is returned to the states based on the level of hunter and angler participation in each state. Last year, Wyoming Game and Fish received $13.6 million from the tax.

Those who have discussed a tax on recreational goods suggest that items as simple as birdseed can be taxed. Sleeping bags and spotting scopes could be taxed as well. The revenue could go to WGFD or to a separate fund aimed at wildlife and habitat conservation.

Lottery funds

The Wyoming Legislature approved the creation of a state lottery in 2013, and tickets will go on sale in June 2014. While some states earmark a portion of lottery revenue for conservation purposes, Wyoming does not. The first $6 million in revenue raised from the lottery will be distributed to towns and counties according to sales tax distribution formulas. Revenue generated after that will go into the state Permanent Land Fund’s Common School Account.

Many other ideas have been investigated, as reported in a December 2012 Wyofile story:

Conversations with outfitters, hunters, legislators, conservationists, and wildlife managers produced a number of suggestions, none of which seemed bulletproof: license plate sales (not nearly enough revenue), a lodging tax (targeting bird watching tourists and the like), a portion of fuel taxes (competing with the Highway Department), a piece of abundant mineral severance taxes (the state’s cash cow, but only so many teats), a higher subscription price on the publication “Wyoming Wildlife” (that might pay for one truck’s annual fuel bill) and voluntary purchases of conservation stamps by non-hunters (ah, volunteerism – hasn’t solved the problem in Idaho).

Governor Matt Mead has assembled a special task force to address the Wyoming Game and Fish budget crisis. They will be tasked with proposing solutions for a broader funding approach for Game and Fish. The task force is expected to convene soon.

This analysis of trapping was made possible through funding from the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and multiple other donors to Wyoming Untrapped.

Endnotes:

1 Jim Hardee, Fur Trade in Wyoming, Wyoming State Historical Society, http://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/fur-trade-wyoming

2 Hank Fischer, Wolf Wars, 2003, p. 13-18

3 WGFD, Annual Report of Small Game, Upland Game, Waterfoul, Furbearer, Wild turkey & Falconry Harvest, 2012

4 The Wildlife Society, Traps, Trapping and Furbearer Management: A Review, 1990.

5 Wyoming Game and Fish Commission Annual Reports, 2003-2013, http://wgfd.wyo.gov/wtest/WGFD-1000485.aspx

6 Billings Gazzette, Demand for fur has market at 30-year high, trappers say, Dec. 25, 2013

7 Wyoming Game and Fish Commission, Furbearing Animal Hunting or Trapping Seasons, through July 31, 2014

8 Born Free USA, State Trapping Report Card, 2012 http://www.bornfreeusa.org/a10_trapping_reportcard.ph

9 Born Free USA, Exposing the Myths: The Truth About Trapping http://www.bornfreeusa.org/facts.php?p=53&more=1

10 Animal Protection Institute, Cull of the Wild, 2004

11 WGFD, Annual Report, 2013, p. xv. http://wgfd.wyo.gov/wtest/Departments/WGFD/pdfs/WGFDANNUALREPORT_20130005237.pdf

12 WGFD, Game and Fish Seeks Feedback on Budget Cuts, July, 2013 http://wgfd.wyo.gov/web2011/NEWS-1001546.aspx

13 Wyoming Department of Administration and Information, Gross Domestic Product for Wyoming, 2012, https://www.google.com/#q=wyoming+economic+analysis+division

14 National Park Service, National Park Spending Effects, 2012, http://www.nature.nps.gov/socialscience/docs/NPSVSE2012_final_nrss.pdf

15 Wyoming Office of Tourism, Wyoming Travel Impacts, 2012 http://www.wyomingofficeoftourism.gov/research-and-reports/annual-reports/

16 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wild-Associated Recreation, 2011 http://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/fhw11-wy.pdf

17 Minnesota Legacy Fund http://www.legacy.leg.mn