How beavers became North America’s best firefighter

BY BEN GOLDFARB

PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 22, 2020

The American West is ablaze with fires fueled by climate change and a century of misguided fire suppression. In California, wildfire has blackened more than three million acres; in Oregon, a once-in-a-generation crisis has forced half a million people to flee their homes. All the while, one of our most valuable firefighting allies has remained overlooked: The beaver.

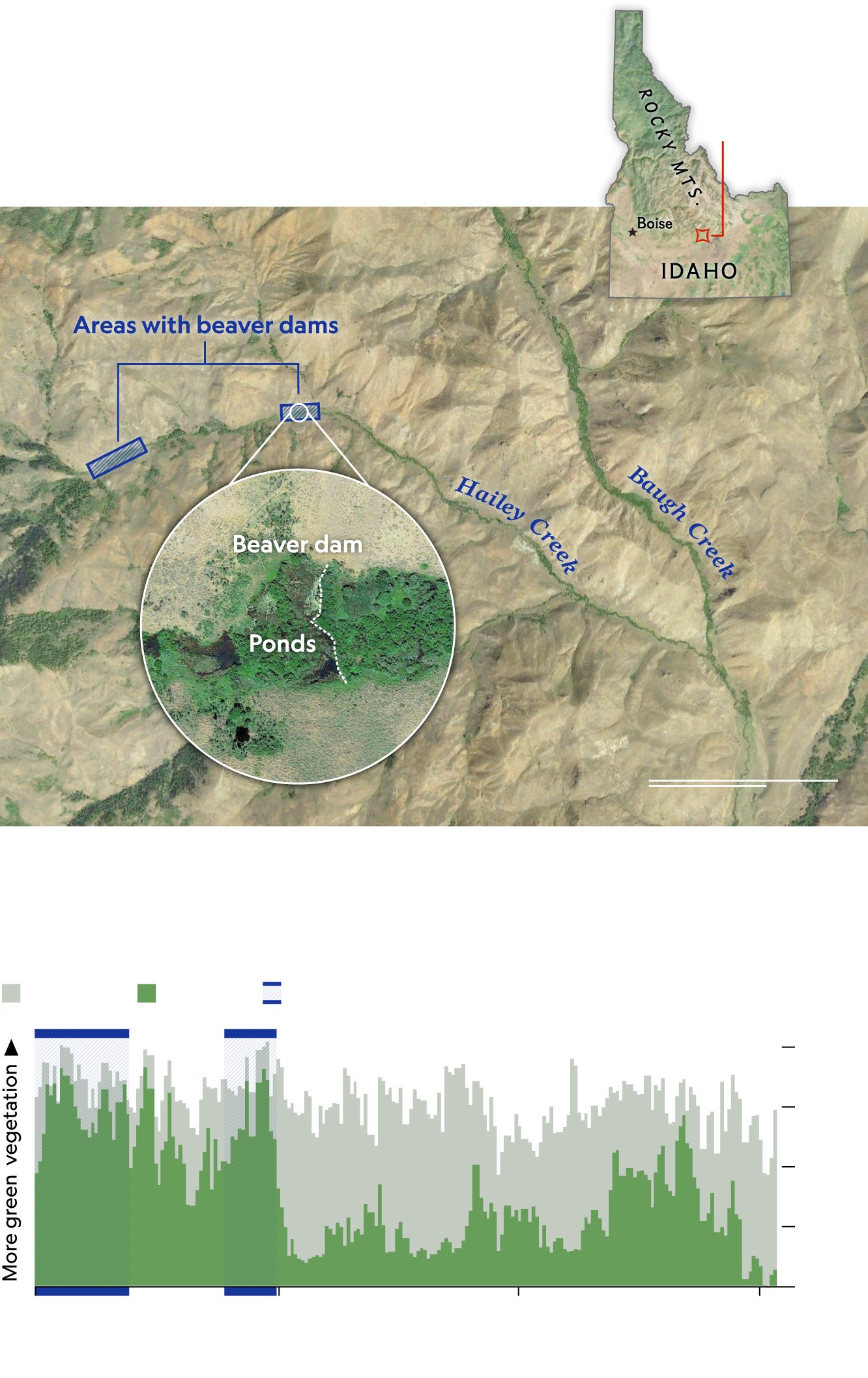

A new study concludes that, by building dams, forming ponds, and digging canals, beavers irrigate vast stream corridors and create fireproof refuges in which plants and animals can shelter. In some cases, the rodents’ engineering can even stop fire in its tracks.

“It doesn’t matter if there’s a wildfire right next door,” says study leader Emily Fairfax, an ecohydrologist at California State University Channel Islands. “Beaver-dammed areas are green and happy and healthy-looking.”

For decades, scientists have recognized that the North American beaver, Castor canadensis, provides a litany of ecological benefits throughout its range from northern Mexico to Alaska. Beaver ponds and wetlands have been shown to filter out water pollution, support salmon, sequester carbon, and attenuate floods. Researchers have long suspected that these paddle-tailed architects offer yet another crucial service: slowing the spread of wildfire.

“It’s really not complicated: water doesn’t burn,” says Joe Wheaton, a geomorphologist at Utah State University. After the Sharps Fire charred 65,000 acres in Idaho in 2018, for instance, Wheaton stumbled upon a lush pocket of green glistening within the burn zone—a beaver wetland that had withstood the flames. Yet no scientist had ever rigorously studied the phenomenon. (See California’s record blazes through the eyes of frontline firefighters.)

“Emily’s study couldn’t be more timely,” says Wheaton, who wasn’t involved in the research. “This points toward the importance of nature-based solutions and natural infrastructure, and gives us the science to back it up.”

Then, using a statistical measure of plant health, they calculated the lushness of the surrounding vegetation before, during, and after the fires. Unsurprisingly, thriving, well-watered plants tended to appear vivid green in the satellite photos, while dry plants looked comparatively brown. (Read more about how wildfires get started—and how to stop them.)

A green, hydrated plant, of course, is also less flammable than a desiccated, crispy one. And that’s what makes beaver ecosystems so fireproof. In beaver-dammed stream sections, Fairfax and Whittle found, vegetation remained more than three times lusher as wildfire raced over the creek. Beavers had so thoroughly saturated their valleys that plants simply didn’t ignite.

These lifeboats don’t merely protect beavers themselves: A broad menagerie—including amphibians, reptiles, birds, and small mammals—likely hunker down in these beaver-built fire “refugia,” Fairfax says. Although wildfire is a vital force that rejuvenates habitat for some creatures, like black-backed woodpeckers, it can devastate other animal populations.

Beaver habitat also protects domestic livestock and agricultural lands, adds Fairfax, whose study was published this month in Ecological Applications. “If you have a beaver wetland, your cows can take advantage of that refuge and fare better during wildfire than if you had to pack them out on trailers.”

In addition, beavers may help an ecosystem recover from a wildfire. In northern Washington State, Alexa Whipple, the director of the Methow Beaver Project, found that beavers promoted the recovery of native species, like willow and aspen.

Beaverless streams, by contrast, were more likely to become colonized with invasive plants after a burn. Whipple also found that beaver ponds improved water quality by capturing the phosphorus-laden sediment that runs off torched hillsides. (Learn how wildfires are increasing worldwide.)

“If we have a wetter landscape, we are going to resist fire and recover from it better,” says Whipple, whose results haven’t yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal. “My hope is that wildfire can be the gateway for people to understand the whole suite of benefits that beavers offer.”

Despite all the good that beavers do, thousands are killed every year for flooding roads, cutting down trees, and causing other damage to human property. Employing smarter, more humane policies—using nonlethal flood-prevention devices like “Beaver Deceivers,” for example, and relocating trouble-making individuals instead of killing them—could heal our relationships with beavers and wildfire alike, Fairfax says.

“Strategically embracing beavers in local watersheds could provide reassurance that you have wet soils and wet plants around your town,” Fairfax says. In fact, as her paper’s title suggests, the U.S. Forest Service might want to consider a new animal mascot: Smokey the Beaver.