The philosophical undercurrent is that public land is not truly public. Its rightful owners are people doing useful things with it: drilling, trapping and ranching. That $3.95 billion Wyoming gets from tourism each year — well, that must be inconsequential.

There are few or no consequences for trappers who injure dogs. The last argument is an old Wyoming reliable, the Slippery Slope. If trapping becomes more regulated, why, soon it will be the turn of hunters, followed by fishing, your Friday night steak dinner and — heaven forbid — fly swatters. Yet sometimes, as Freud liked to say, a cigar is just a cigar. It is past time when fellow citizens who trap took responsibility for their actions.

Yes, gentle reader, Vedauwoo can be a tourist trap. Not for you, but for your dog.

It is one of Albany County’s treasures. Next time you approach Laramie from Cheyenne, glance north and take in the unique geology. Granite from the Sherman batholith eroded to form piles of giant boulders that sport fanciful names like Turtle Rock, Bison, Loaf of Bread, Hawk, and Dinosaur Bone. Last weekend I visited this special part of the Medicine Bow-Routt National Forest. It was a sunny cool November day. Vedauwoo was full of walkers, many with dogs, plus cyclists, picnickers, rock climbers, campers and hunters. It is a popular and beloved place.

Being trapped at Vedauwoo is a possibility. It will be a dog, maybe yours. That is because of our state’s archaic trapping regulations. Traps for fur-bearers and predators can be set on or beside public trails, even at Vedauwoo. Trappers are not required to report snared or killed dogs to the Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD). Although not tracked by WGFD, a Wyoming non-profit reports these on its website. The episodes posted are unlikely to be a complete statement of the problem. I doubt many trappers contact Wyoming Untrapped to declare: “Hey, I just killed a trio of St. Bernard dogs”. Yet that is what happened to three dogs near Casper in 2014 on Nov. 30 (Brooklyn) and again on Dec 2 (Jax and Barkley).

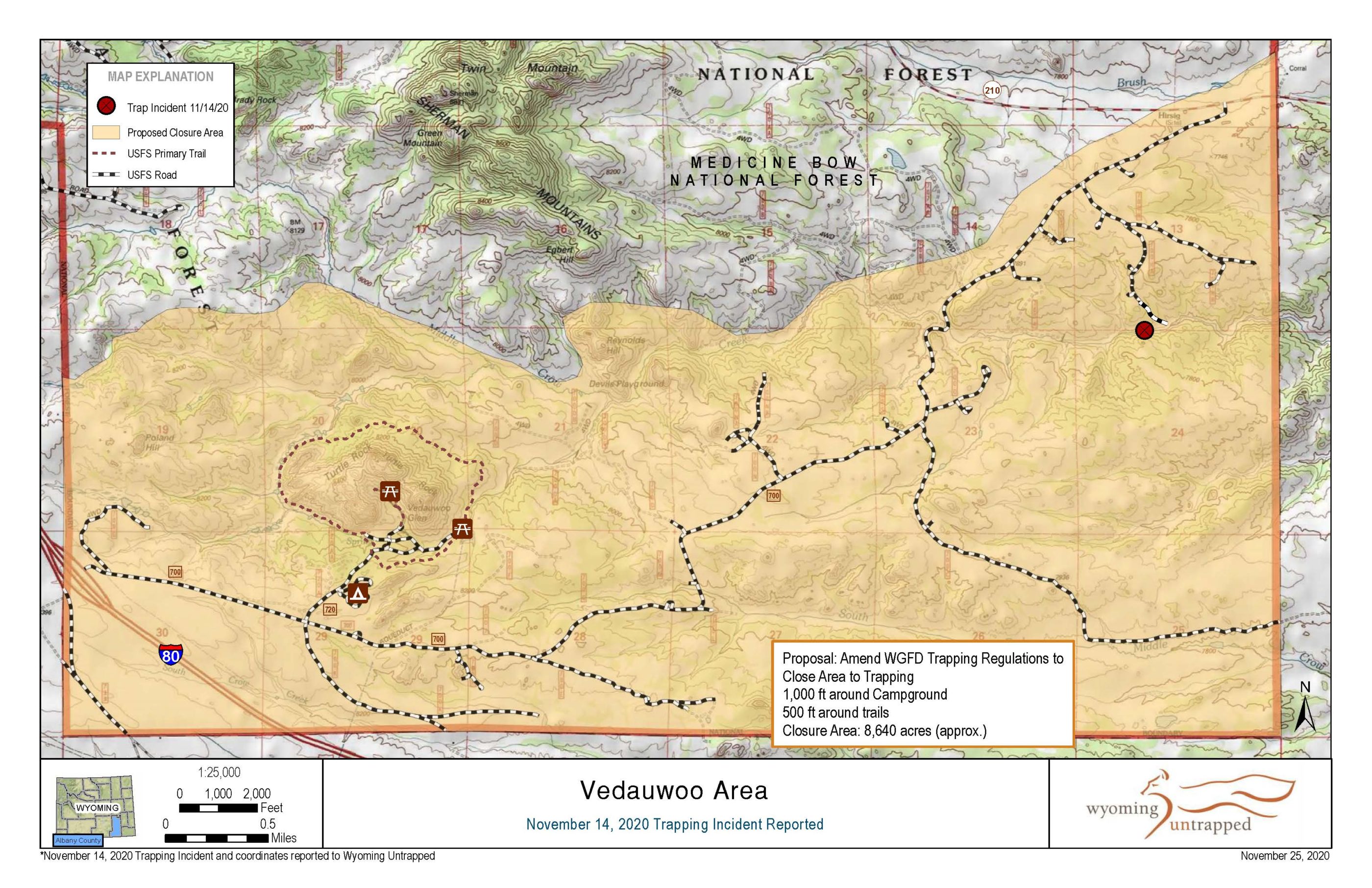

The latest episode occurred in Vedauwoo in November. A dog was caught in a leg hold trap. A WGFD game warden investigated the incident the following week. The trapper set snares and leg hold traps along Middle Crow Creek. The trap was 228 yards from the nearest campsite. The trapper put aluminum flashing in a tree, along with a small scent object. He claimed this is how he trapped coyotes in his home state of Missouri. He acted surprised when the game warden told him that, at least in Wyoming, flashing is used to lure bobcats. He got off with a warning about checking traps more often.

While at Vedauwoo I looked for signs warning the public that traps can be set between October and April. There are none. You are just supposed to know.

The trapping community and some legislators are reluctant to accept that current trapping rules need revision. Resistance comes in several flavors. One is the contention that trappers do the right thing and don’t require more oversight. Moreover, so the argument goes, trapping protects citizens from a tsunami of predators, such as coyotes and assorted fur-bearers. The published science begs to differ but let’s save that for another day. Since WGFD does not require trappers to report each season’s catch, the department and the public are blind to ecosystem impacts.

Another argument is that it is the responsibility of hikers to be trap-aware. This logic dictates that dogs on public lands be leashed. If a dog is trapped or snared, it is on the owner. It implies that responsible owners will attend How to Release your Dog demonstrations, and carry cable cutters and a set tool for Conibear and Magnum traps. Often this argument is combined with some grumbling about out-of-state visitors, the threats to our Western heritage, and a need to extract money from non-consumptive users. The philosophical undercurrent is that public land is not truly public. Its rightful owners are people doing useful things with it: drilling, trapping and ranching. That $3.95 billion Wyoming gets from tourism each year — well, that must be inconsequential.

The trapper set snares and leg hold traps along Middle Crow Creek. The trap was 228 yards from the nearest campsite.

Then there is whataboutism. It goes as follows. A dog owner complains her dog died in a neck snare. The response, mostly recently from WGFD commissioner Schmid, is to the effect of “OK, but what are YOU doing about deer attacked by dogs?” Yet legal provisions exist to address dogs that savage wildlife, in addition to an entire wildlife agency. There are few or no consequences for trappers who injure dogs. The last argument is an old Wyoming reliable, the Slippery Slope. If trapping becomes more regulated, why, soon it will be the turn of hunters, followed by fishing, your Friday night steak dinner and — heaven forbid — fly swatters. Yet sometimes, as Freud liked to say, a cigar is just a cigar. It is past time when fellow citizens who trap took responsibility for their actions.

The modest reforms proffered by Wyoming Game and Fish Department biologists, subsequently improved by a majority of the Wyoming Game and Fish commissioners, come before the legislature’s Joint Travel, Recreation, Wildlife and Cultural Resources Committee on Dec. 8. If your family likes to walk with dogs in places like Vedauwoo, and you prefer to enjoy the vista rather than scan for snares, now might be a good time to speak up.

Dr. O’Toole is a veterinary pathologist in Laramie.

This guest opinion was published in the Casper Star Tribune.